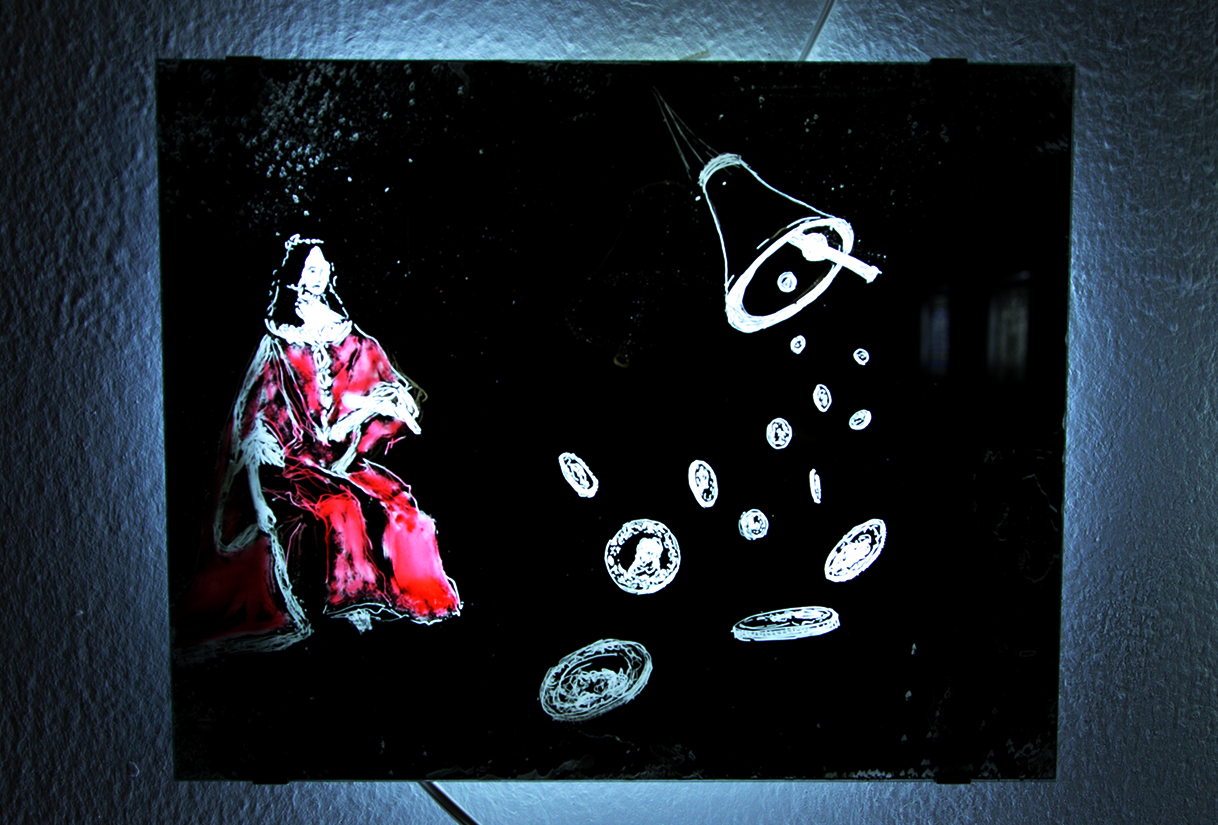

ermine and rosary.

castle borbeck. essen. 2014.

‚When we think objects and circumstances, there must be a place that reflects them.‘ (Kitaro Nishida 1926)

This quote is from the Japanese philosopher, Kitaro Nishida, the founder of the Kyoto School, which sought to connect the traditions of western philosophy with the intellectual legacy of the Far East. In his work ‚The Logic of Place‘, Nishida devises a topological concept of space, that differs from the western idea of an objective and universal space. Space here is not a container, but is constituted of objects, constellations and actions in time.

Nikola Dicke‘s work – Ermine and Rosary – is structured like that. Though she refers to a contemporary place, she speaks of things, events and persons that once were active here, still are even: the High Convent of Essen and its governing Prince-Abbesses. These women, members of the high clergy, were strong women, women with experience and an eventful life story; they were in no way inferior to men. Nikola Dicke thematises this historical context with artistic means and so moves it into the present. It thus requires a poetising form of commemoration, which also accesses the phantasmagorical, the imaginary. The taxonomy of science sorts and describes the factual, and reveals structures in the model. A holistic understanding of the past with the means of art – the graphic animation – condenses the tangible traces and transforms them into meaningful symbols.

(Andreas Brenne)